NY Times Investigative Reporting: Reaching Out to Unknowing Stolen Check Victims

- Anyone with a smartphone can download an app and quickly get access to bundles of stolen checks sold in open forums.

- Banks are shuttering accounts without communicating with their customers

- NYT reporter reaches out to unknowing victims

On the heels of NY Times reporter Tara Siegel Bernard covering the rise of check fraud, colleague Rob Lieber has taken it a step further to investigate the epidemic. In his related article on NY Times, Lieber gains access to these check fraud groups to take a look at how stolen checks on being sold on Telegram.

Lieber notes that the Telegram app is easily downloadable on any smartphone -- making the platform easily accessible to fraudsters. Remember, Telegram is an encrypted messaging platform, making it difficult for law enforcement to gather evidence of crimes. He utilizes his investigative reporting skills to gain access to a group, where he finds a plethora of stolen checks for sale.

Understanding the Stolen Check Marketplace

It's important to understand that these fraudsters are sophisticated, and not blatantly announcing their intentions. Lieber notes that there are specific code words utilized to indicate the sale of stolen checks, and once an individual understands the lingo, the underground stolen ecosystem is easily accessible.

The Telegram forums selling stolen checks are easy to find if you know the code words to search for. I didn’t, but bank security consultants do, and they provided me with a few to try. I spent just a few minutes looking and immediately lost count of the number of checks I found for sale.

The marketplace is something that banking fraud professionals and readers of our blog are familiar with, starting with obtaining stolen checks -- with robberies of mail carriers and mailboxes being a major source. Once obtained, the checks are sold on these marketplaces (like the ones Lieber accessed on Telegram) and check fraud is perpetrated through washing or other methods.

Lieber provides information from Socure, a company that sells digital identity confirmation services to banks, that they believe "there may be nearly 2.5 million so-called synthetic identity accounts out there in the world, sitting in wait for nefarious dealings." These accounts help fraudsters deposit the stolen funds.

Shuttered Bank Accounts

Banks are taking action to close down accounts identified with fraudulent behaviors. Most likely, this is done utilizing transaction analytics systems or more advanced behavioral analytic systems. The system identifies suspicious behaviors or transactions, and closes down the accounts. While the actions seem logical, the execution is where the issues arise.

When banks are not actively communicating with their customers, many of the account holders of these shuttered bank accounts only become aware this has occurred when they attempt to utilize the funds at a retail location. What's even more concerning is that they do not know the reasons why their accounts have been closed.

This lack of communication causes what Lieber characterizes as "chaos." Imagine you're at a coffee shop trying to get your morning "cuppa Joe" as per your routine -- only to find your account closed or frozen and your caffeine fix denied. It's incumbent upon banks to do better in reaching out to their customers to inform them of actions taken to mitigate disturbances.

Reaching Out to Victims

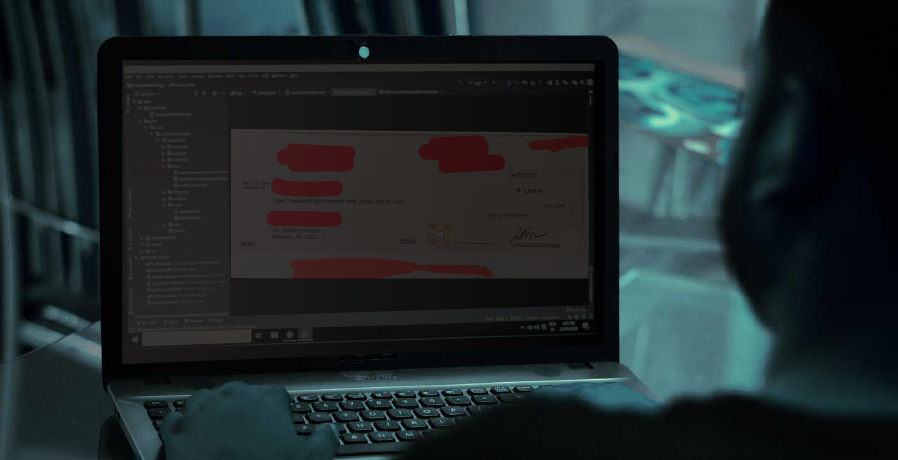

As part of his investigation, Lieber boldly takes action by capturing information from images of 20 checks being sold and reaching out to the victims. Not unexpectedly, they were not aware of that their checks were stolen. Many of the checks had not reached their intended recipient, and, in some cases, the checks were older and deposited into fraudsters' accounts without the knowledge of both the payee and payor.

The article recounts several interactions and details everything from possible insider fraud -- where check images are saved and possibly stolen by insiders -- to checks intercepted before reaching the intended payee. Lieber reached out to one of our favorite #FraudFighters for his thoughts:

While my random sampling of stolen checks numbered just 20, the resulting confusion was enough to leave experts scratching their heads. “This is more convoluted than I even could have thought,” said Frank McKenna, chief fraud strategist at Point Predictive, which uses data to help clients prevent theft.

He asked whether anyone had considered another possibility: that post office insiders steam open envelopes, remove checks, take pictures of them, reseal the envelopes, send the checks on their way and then go and sell the images of the checks. Nope, and so noted!

We applaud the NY Times for their efforts to illuminate for the general public this growing problem. While banks are in the process of adopting innovative technologies like behavioral analytics, image forensic AI, and dark web monitoring to better protect their customers from check fraud, it's important for people to remain aware of potential threats in order to better protect their checks.