Cash is Almost Dead, According to MIT

Source: MIT Technology Review

Is cash becoming an endangered species? And, if so, is that good?

Mike Orcutt, an associate editor at MIT Technology Review, has written what he calls an elegy for cash at the MIT Technology Review site, and includes some points to ponder regarding whether the demise of cash could actually be a negative development, as well as some potential significant consequences when high tech solutions displace bearer instruments.

A bearer instrument is, of course, a type of fixed-income security in which no ownership information is recorded and the security is issued in physical form to the purchaser. The holder is presumed to be the owner, and whoever is in possession of the physical bond is entitled to the coupon payments. If you have a dollar, it's your dollar because you have possession of the physical object. Same with a check signed over to you.

Orcutt suggests that there is a certain freedom there that we lose when making digital transactions.

Without cash, there is “no chance for the kind of dignity-preserving privacy that undergirds an open society,” writes Jerry Brito, executive director of Coin Center, a policy advocacy group based in Washington, DC. In a recent report, Brito contends that we must “develop and foster electronic cash” that is as private as physical cash and doesn’t require permission to use.

So, there's the privacy issue. But, what about the fact that most electronic payment products -- like Alipay, Zelle, PayPal, and Venmo -- are run by private firms?

We call banknotes and coins “cash,” but the term really refers to something more abstract: cash is essentially money that your government owes you. In the old days this was a literal debt. “I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of …” still appears on British banknotes, a notional guarantee that the Bank of England will hand over the same value in gold in exchange for your note. Today it represents the more abstract guarantee that you will always be able to use that note to pay for things.

The digits in your bank account, on the other hand, refer to what your bank owes you. When you go to an ATM, you are effectively converting the bank’s promise to pay into a government promise.

Most people would say they trust the government’s promise more, says Gabriel Söderberg, an economist at the Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden. Their bet—correct, in most countries—is that their government is much less likely to go bust.

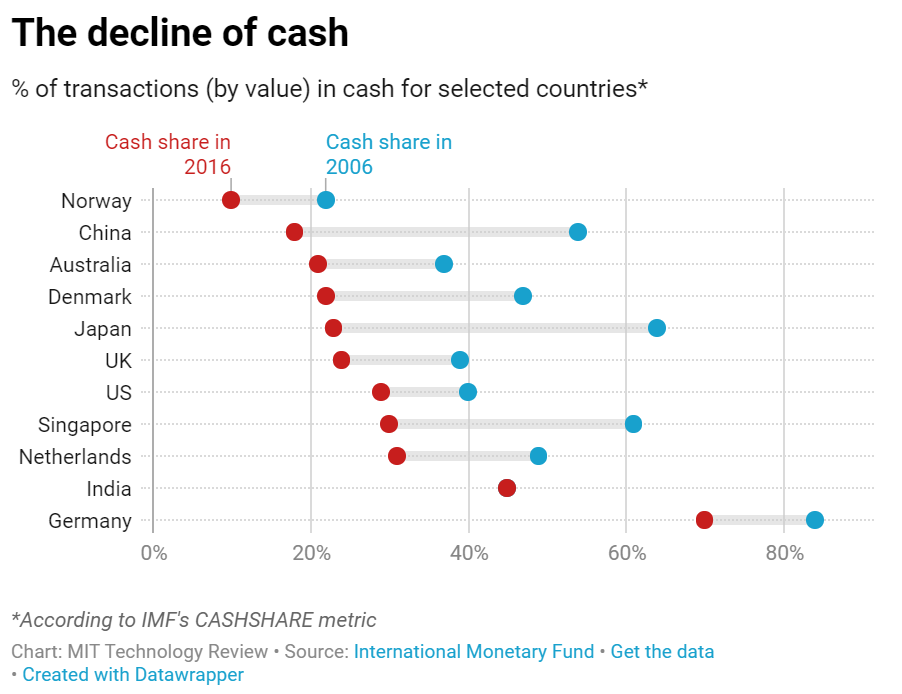

Not all countries are adopting digital payments at the same rate, but China, for one, is moving fast. It’s been estimated that mobile payments made up more than 80% of all payments in China in 2018, up from less than 20% in 2013.

However, it's a bit early to count out cash. ATMs remain very popular, and cash is king in establishments like casinos. There is also the issue of legislation. In 2019, San Francisco officials voted to require brick-and-mortar retailers to take cash as payment, joining Philadelphia and New Jersey in banning a growing paperless practice that critics say discriminates against low-income people who may not have access to credit cards.

Also, witness the success of our partners, Cummins Allison, who create specialized scanners designed to scan cash and checks. In addition to serving the normal -- and steady -- demand created by ongoing paper currency usage, they have found a fertile market in providing scanners to banks in states where cannabis is legal, since it is a very cash-based industry.

The end of cash and paper transactions? Hardly!

The U.S. treasury needs to start minting silver dollars to raise the value back up.